This exhibition titled “Pink Ladies'' highlights works of British Pop artists in and around the 1960’s, an art movement in which appropriation of popular culture and mass media imagery was a defining feature. Coinciding with the peak of the British Sexual liberation movement, critique of societal consumption of the female figure was a point of examination for many Pop Artists. This collection of works all utilize the female figure and nod to femininity through the use of pink. A color rich in history in western culture surrounding femininity, feminism, fetishism and relationship between consumption and women.

The first and most basic function of the colour is to denote something as feminine. This can be observed for stereotypically feminine products, where the color serves an advertisement to female consumers. Pink has associative roots dating back to the 1920s, as a color for little boys. As blue shifted to the color of Naval uniforms, a male profession, a cultural desire to maintain a gender binary began to string a narrative of blue as masculine and therefore pink a mark of femininity.

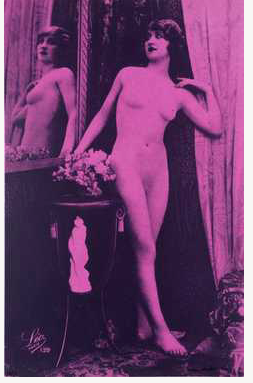

Popular associations go hand and hand with typically socialtally structured female characteristics, sweetness, cheekiness and allure. In the 1940’s Hollywood actresses normalized the cosmetic industry and created a culture around communism and forever tied an ideal of consumerism and female sexualization together. Elsa Schiaparelli introduced “shocking pink” to cosmetics, a dark shade only for the bold. Significant as historically brightness and saturation promotes sexual connotations. Highly saturated shades indicate negative ones of artificiality and cheapness, which index working-class femininity. By contrast, adding white to the shade triggers cultural associations of innocence, which in turn is culturally equated with an absence not only of guilt but also of desire and sexual experience.

By the 1960s British Pop Art had taken on its full form, particularly flourishing in Liverpool, as the center struggled to transform their industrial production under post-industrialism. This complicated relationship with production became the perfect ground for cultural icons of the sixties, celebrities who’s imagery and mass fascination would become the inspiration for many pop artists.

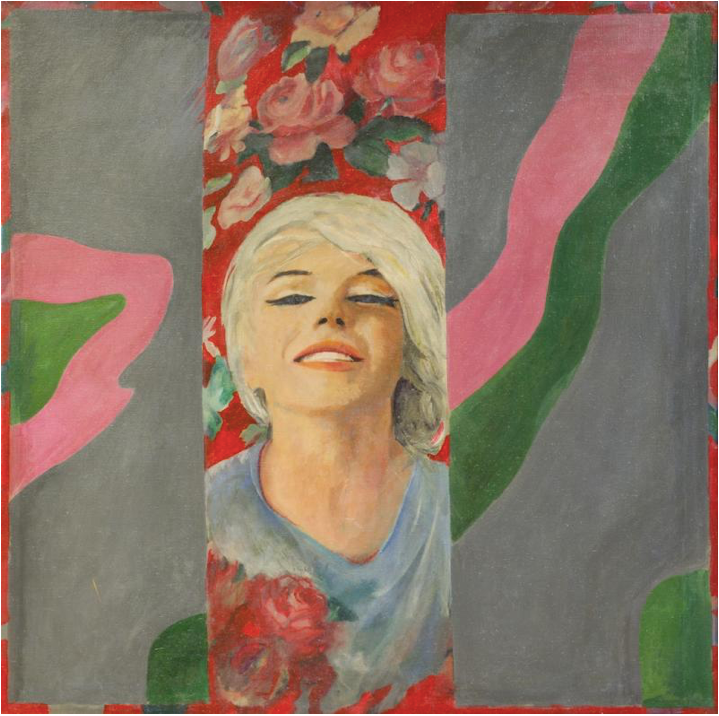

The material of pop art itself was the world of mass culture, a culture that allowed women themselves to function as markers of culture. Stars like Marilyn Monroe, Brigitte Bardot and Elizabeth Taylor being impossibly idealized. Women themselves were once made by previous decades to be unattainable and supremely housewife material as seen in Sir Eduardo Paolozzi’s work were now equally objectified, yet more overtly sexual.

Sexual liberation and an evolving, feminist consciousness fundamentally changed life in England. The contraceptive pill’s invention in 1952 and later ban by the Catholic church in 1964 was pivotal in the women’s rights movement in England. The pill lifting the curse of the female sex with promise of euphoric freedom, inspired a push back at the historical hold men have over the female body.

In these works pop artists utilize the cultural ideas of pink intertwining them with the social atmosphere surrounding women in England in the 1960s.

Real Gold. 1949. Sir Eduardo Paolozzi. Printed papers on paper 282 x 410 mm. Tate.

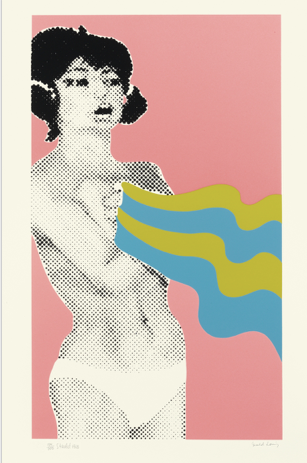

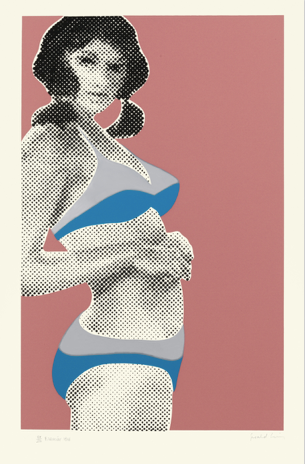

Brigitte Bardot. 1968. Gerald Laing. Screenprint in colors. 58.6 × 89 cm. Sims Reed Gallery, London

After studying at Saint Martin’s School of Art in London Gerald Laing launched his career into the ready popular Pop Art movement. In line with movement borrowing iconography from popular culture and the visual language of printed form, Laing's Silkscreen print of Bridgett Laing taps into comic and newsprint style visual language pairing his highly detailed technique with his subjective choices for his male gaze centric passions. Bridget Bardow, a former French actress known particularly well for playing sexually emancipated characters is one of the better known sex symbols of the late 1950s and 1960s.

Bardot’s beauty and celebrity combined with the abstract nature of geometric shape highlights her sex symbol status through a solid circle of color - pink. Labeling her with a geometric shape literally transforms her status and figure into a symbol, a highly gender one at that.

The piece evolved into his later 1960s works Baby Baby Wild Things, 1968, in which he again appropriated the female figure comparing the smooth and geometric perfection of the body’s to that of a formula one race car. Pink ink serves as a shell to the highly desirable and highly gendered and objectified subjects.

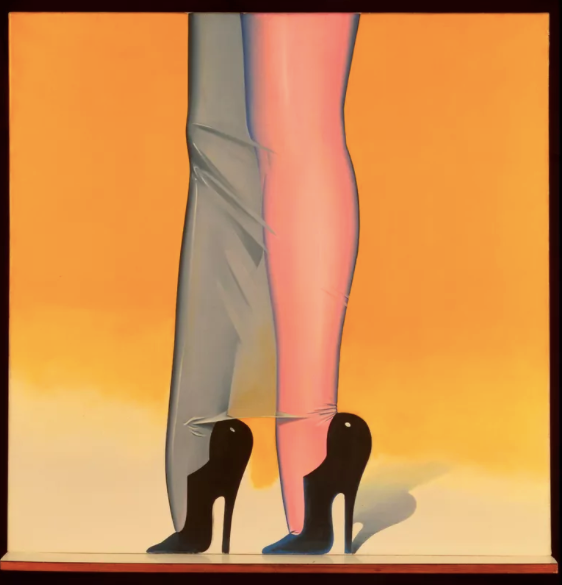

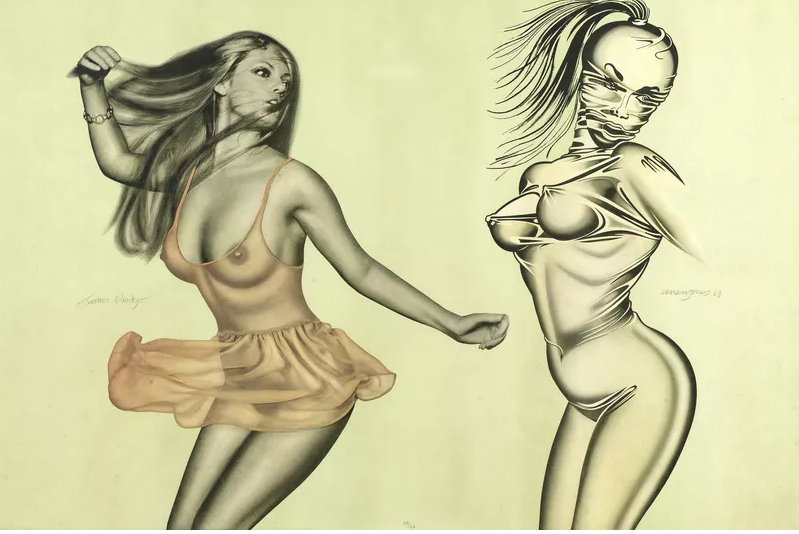

The 1960s became the time of the liberated women. A liberation that inevitably put women in an impossible dilemma, to liberate oneself was to subject oneself to fetish. Cinema, Television, and magazines emphasized this female fetish, and artists like Allen Jones claim to work with this liberation and fetishization.

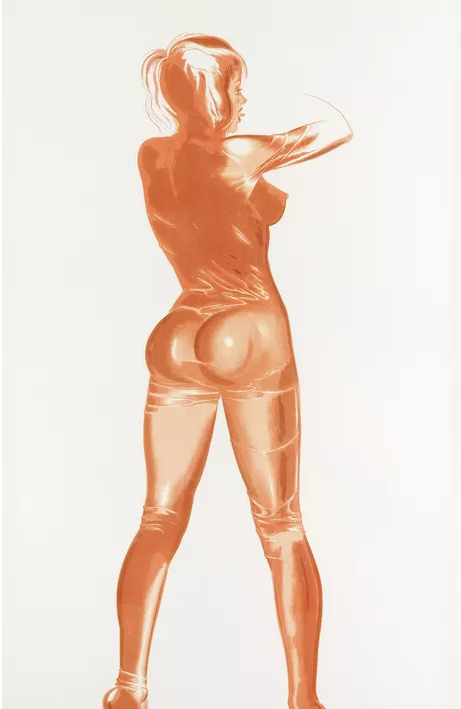

Allen Jones and his artwork are ever relevant to discourse surrounding social constructs of gender and media obsession with the body. He is notoriously critiqued for his exploitation of the female body and appropriation of sexual imagery.

After attending the Royal Academy of Arts he began his career amidst the peak of British pop art. The male gaze becomes the vessel in which he paints his subjects. Painting raunchy female forms of no one in particular, but an as idealized, stylized and three dimensional figure as possible. Drawing on non-fine art imagery like 1950s fetish magazines,advertising, comic strips, catalogs and girlie magazines.

On the left the figure is wrapped in a seemingly plastic coating, similar to that a toy or physical shelf product would be, implying the figure is ready to be consumed. In a different but entirely similar way Jone’s paints the figure to the left in a sheer lingerie style pink dress, raising the timely 1960s association of pink and the sexually confident female. Both figures are stylistically perfect as if assembled and fitted ready to be consumed by male gazers.